Wang Calculators - History

Dr An Wang was born in China and trained there as an electrical engineer, graduating just prior to WWII. At the end of the war he obtained a scholarship to study in the United States and upon arrival he audaciously applied to Harvard University. To his surprise, was accepted. He completed a Masters degree, and then a PhD, neither of which were in the fields of electronics or computing.

After completing his PhD Dr Wang applied somewhat by chance for a job at the Harvard University Computation Laboratory. He was successful and Dr Howard Aiken gave him the task of investigating novel means of data storage. Howard Aiken had developed the Harvard Mark I calculating machine and was already chafing against the limitations of early storage technology. In his biography An Wang says that within weeks he’d had a breakthrough and could see the basis of a new form of data storage based on magnetic cores.

An Wang’s idea was for the cores to be placed in line and for data pulses to be clocked along this line to form an electronic version of delay line memory. He generously and very clearly attributes to Howard Aiken the idea of placing the cores in an x-y matrix where each core would store the state of one binary bit. This was the design which resulted in core memory becoming one of the most important technologies for the first generations of electronic computers.

Dr Wang had a strong entrepreneurial drive and while at the Computation Lab he was developing electronic circuit modules for possible sale. In 1949 he decided to apply for a patent on the core memory devices that he had been working with. He discussed this plan with Dr Aiken and received no objection, so he proceeded and was awarded what turned out to be a fundamental patent on the basic principle of magnetic core memory. In 1951 he left the Computation Laboratory and established Wang Laboratories as a supplier of electronic logic modules and a designer of digital logic solutions.

Wang Laboratories initially produced bespoke systems including machine tool controllers and a printing-press preprocessor that greatly speeded the production of justified text blocks. During this time Dr Wang developed an electronic method for generating logarithms and antilogarithms. Electronic multiplication and division had until then been a slow and complex process but Dr Wang’s logarithmic functions allowed multiplication and division to be reduced to addition and subtraction. The logarithmic methods would become the basis of Dr Wang’s first series of highly successful products. During this period Dr Wang also had a bruising series of negotiations with IBM regarding their use of core memory and his patent. It appears that IBM adopted very aggressive tactics and one result may have been to strengthen Dr Wang’s desire to succeed as an entrepreneur, perhaps with the aim of one day displacing IBM itself.

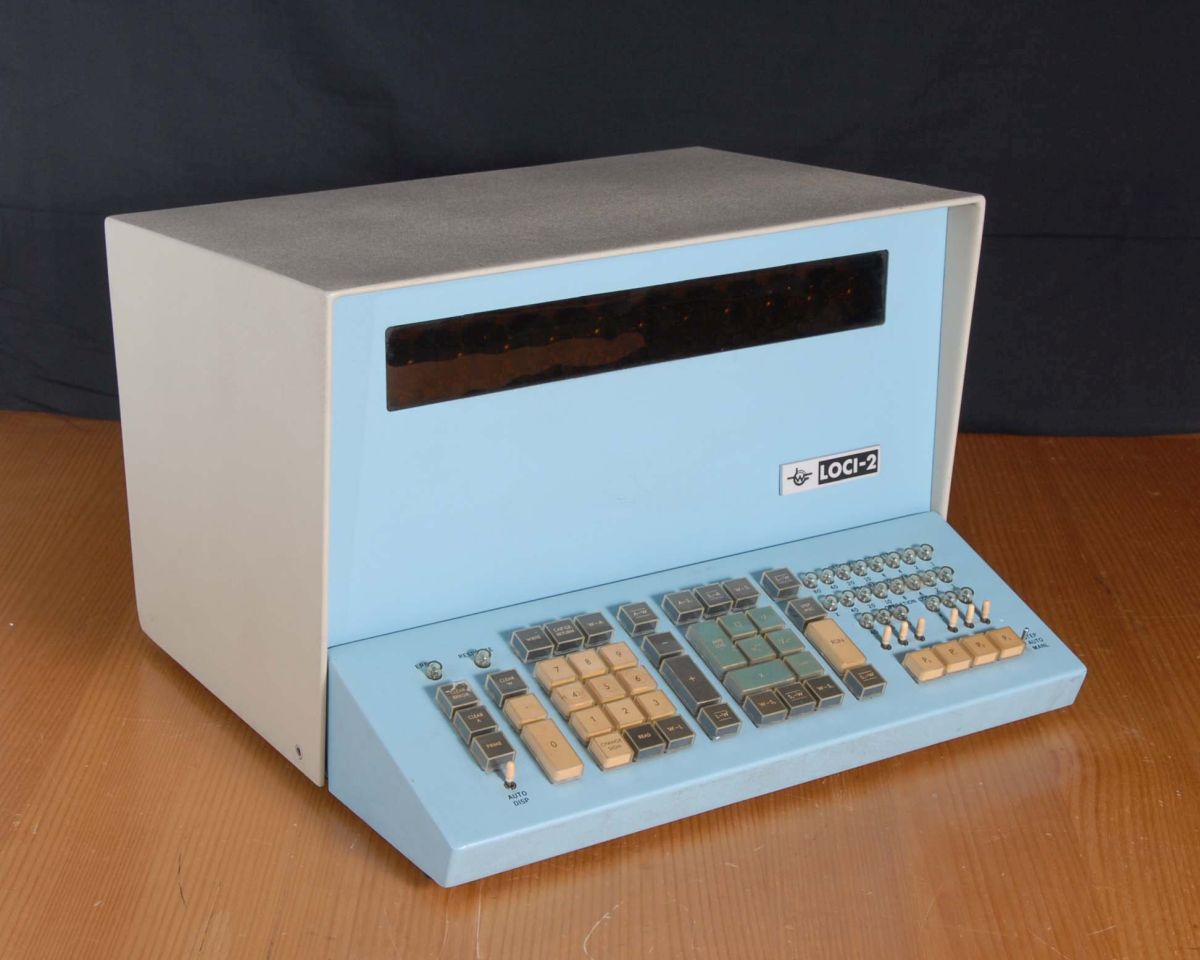

In the early 1960s Wang Laboratories produced one of the world’s first desktop digital calculators. The company was well placed, possessing Dr Wang’s logarithmic calculation methods and having a deep familiarity with core memory technology. This calculator was the LOCI, one of three or so machines that vie for the title of first personal electronic calculator.

Wang LOCI Calculators

The LOCI machines were the first calculators based on Dr Wang’s logarithm circuits. They came to market in 1964, with the name being derived from “Logarithmic Computing Instrument”. They were complex to look at and had a peculiar operating method that was based on the underlying engineering and paid little heed to user interface design. Nevertheless, scientists and engineers readily understood the logarithmic approach and appreciated the calculating power available from a machine that operated on these principles.

The LOCI-1 was a short-lived first version, rapidly replaced by the LOCI-2.

The LOCI-2 has two significant distinctions among all other first generation machines. Firstly, it is programmable with loop and branch abilities. Secondly, it has an interface connection that allows data to be input, processed by the calculator and then output. These features made the LOCI more than just a desktop calculator, it could also be used in process control and data acquisition/analysis. No doubt Wang Laboratories’ past experience in these fields suggested the use of LOCIs in this way, an application that was overlooked by almost all other calculator companies. Wang Laboratories had a department that assisted in the design of LOCI based data acquisition and processing systems and one interesting system that resulted was a spacesuit testing system that was used by NASA throughout the 1960s.

Wang 300E Series Calculators

Wang Laboratories introduced the 300 Series in 1966. The 300 series machines retained the power of the logarithmic calculation method but were smaller and provided increasing calculating power. The packaging was more appealing with a compact desktop keyboard and separate electronics box but the user interface remained rather unfriendly with terse keyboard symbols and puzzling features like two sets of “+” and “-” keys. The 300 series machines were readily understood and appreciated by scientific and technical users. They rapidly became very successful and expanded into a family of more powerful machines and associated peripherals such as extended storage boxes, teletype, paper tape and CRT interfaces. The final stage was represented by the 370 and 380 series programming keyboards that could store and execute programs from punched cards or magnetic tape cartridges.

The 200 Series

The 300-series were less popular in business and non-technical markets because of a side effect of the logarithmic approach. Most numbers do not have finite logarithmic representations and logarithmic operations generally involve approximations, to 14 digits of precision in the case of the 300 series. Scientific, engineering and technical users understood these approximations and recognised that the answers were very satisfactory for building bridges, surveying land or launching rockets.

Business and non-technical users were disturbed however, when “10 divided by 2” produced the answer “4.9999999999999”. Wang responded with the 200 series, which added rounding-off logic to the 300 electronics so that more familiar results were displayed.

The 300SE Series

The 300 series machines were very successful but rather expensive. A mid-range 300 system cost about $2000 in 1967, similar to a Ford pickup truck. The SE series added a form of multiplexing onto the 300 electronics so that four keyboards could be attached to a single electronics box, allowing four users to work (almost) simultaneously.

The multiplexed solution was not perfect and it was possible for one user to interact with another under some circumstances. Nevertheless, the SE series met a demand for Wang calculator power at lower prices. Indeed, splitter plugs were available so that multiple keyboards could be plugged into each of the SE unit’s four sockets, allowing up to ten or more users on a single SE box. Bearing in mind that all users on a single SE socket could see and alter each other’s work, the potential for departmental chaos is obvious.

The 370 and 380 Programmers

The 300 series reached its peak with the 370 and 380 Programming Keyboards. These keyboards contained logic which added looping, logical tests, jumps and subroutine calls. The 370 keyboard read its program from punched cards while the 380 used loops of magnetic tape in cartridges. These keyboards converted a 300 series electronics box into a small computer. Processing speed was not high and the 380 in particular suffered from slow access to its program with a sequential search of the entire tape being done whenever a program branch was taken. Nevertheless, these systems provided very useful computer power at far less cost than a 1960s computer, and with desktop convenience. The programming keyboards also featured an input-output bus which could communicate with a string of peripheral devices. These included Data Storage units with up to 256 registers, typewriter and teletype output, paper tape interface and even a CRT interface to perform real-time graphical output.

The 700 Series

Wang’s dominant position with the 300 Series was disrupted when Hewlett-Packard gave Dr Wang a private demonstration of their upcoming 9100A calculator. It was obvious that the 9100 would render the 300 series (and indeed all other 1960s calculators) obsolete and Wang Laboratories embarked on a crash program to find a response.

The 700 series was the result, re-purposing a microcode-driven hardware design that was intended for a small computer. Replacing the microcode allowed that hardware to become a sophisticated calculator, released in 1969. Great credit must be given to Harold Koplow who designed the 700 series microcode and went on to become Wang’s microcode guru.

The 700 series machines were successful but suffered from their late release after H-P’s 9100 series. Wang trailed HP in further development, perhaps because the platform underlying the 700 series was not originally designed for high-end scientific calculators. Wang lost its leading position in the calculator market around this time and never regained it.

The 600 and 500 Series

The 600 and 500 series were improved versions of the 700 series, the 600 series appearing in 1972. The 600 and 500 series used almost the same case and internal construction. The microcode-driven electronic logic was essentially the same as the 700 series, with certain improvements. Integrated circuit memory was used by Wang for the first time, replacing magnetic core and allowing a much larger RAM store to be provided.

The 400 Series

The 400 series represented Wang’s move to MSI/LSI IC technology. By the early 1970s integrated circuit technology was advancing rapidly and electronic production was becoming faster and cheaper. Wang’s hardware skills would become less relevant while microcode and software development would become more important to success.

The 400 series were smaller, cheaper and yet more powerful than the 700/600/500 series.

Although Wang had been the dominant player in electronic calculators for nearly 10 years, it fell behind Compucorp for sophisticated microcoded machines and did not pursue H-P as a massive new market for advanced pocket-sized calculators was defined. Japanese manufacturers were beginning their flood of small, cheap 4-function machines at the same time and this left little space for Wang.

The 400 series was Wang’s last major calculator family. There were a few derivative machines but Dr Wang took an active decision to leave the calculator business and to concentrate on minicomputers, a decision that proved just as wise as his decision to enter the calculator business, and very much more profitable.